Emergency calls can fail in quiet ways. A busy PBX, a noisy network, or a full paging zone can hide an SOS when people need it most.

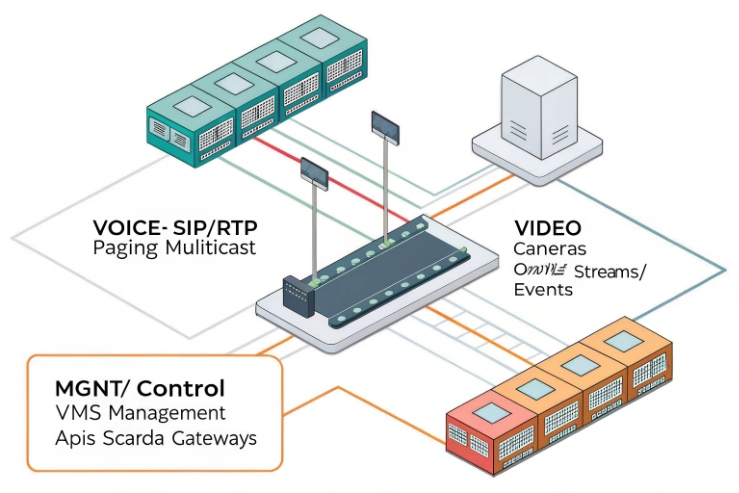

Emergency call priority works when SIP signaling, PBX rules, paging tiers, and QoS act as one system. The phone starts the alarm, but the platform enforces precedence and the network delivers it fast.

Priority is a layered design, not a single checkbox?

Priority vs preemption: do not mix them

Priority means an emergency call gets handled first. Preemption means the emergency call can push a lower call out of the way. Many systems claim “priority” because they can place a call in a special queue. True preemption is rarer. A project becomes stable when the spec says which behavior is required.

A simple rule helps: use priority for most workflows, and use preemption only where the control room must always be reachable, even during peak load.

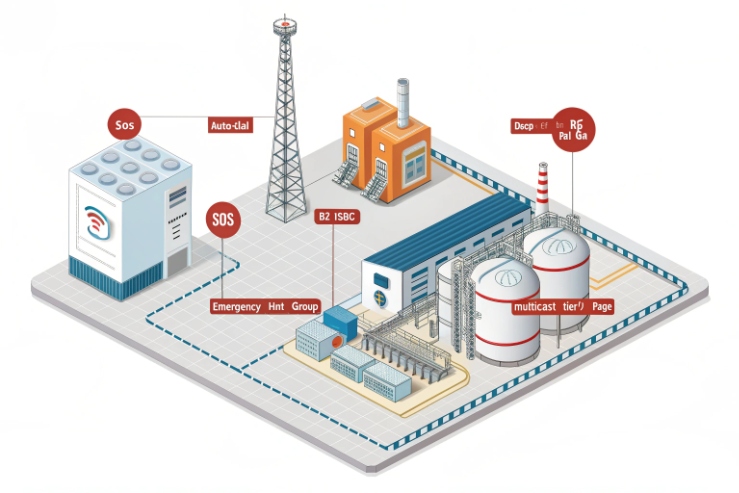

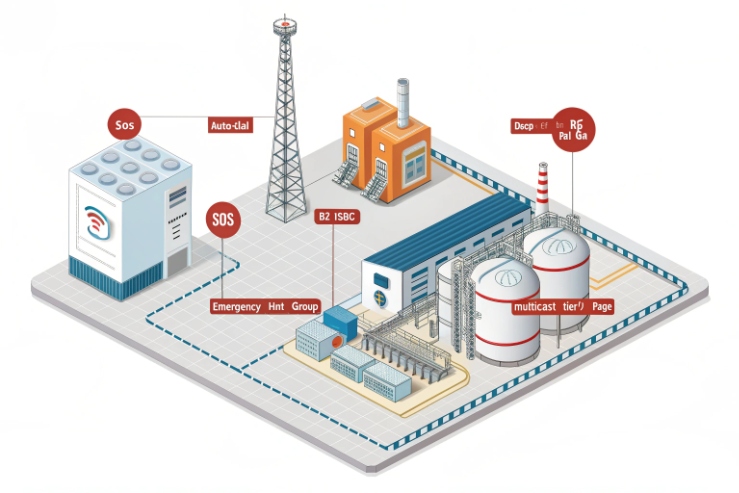

Define the emergency “signal path” from button to operator

An explosion-proof telephone normally triggers emergencies in one of these ways:

-

SOS button hotline auto-dial 1 to a control room or dispatch group

-

Hotline key calls a fixed number

-

Relay output closes to trigger a PLC alarm

-

Paging starts to a zone speaker group

The best design uses two paths at the same time:

1) A voice path (SIP call to dispatch)

2) A control path (PLC/VMS alarm, or PAGA trigger)

This dual path prevents “silent failure.” If SIP is delayed, the PLC alarm still tells the operator where to look.

A practical “priority stack” that works in plants

In DJSlink-style industrial projects, the priority stack is written in four layers:

| Layer | What it controls | What to configure | What to measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIP signaling | How the PBX treats emergency calls | Resource-Priority tags, dial plan rules | Call setup time under load |

| PBX logic | Who rings first and how long | queues, ring groups, paging overrides | Answer rate and time-to-answer |

| Paging delivery | Who hears the alert | multicast tiers, zone rules, fallback | coverage and delay per zone |

| Network QoS | How fast packets move | DSCP, voice VLAN, switch queues | jitter, loss, latency during bursts |

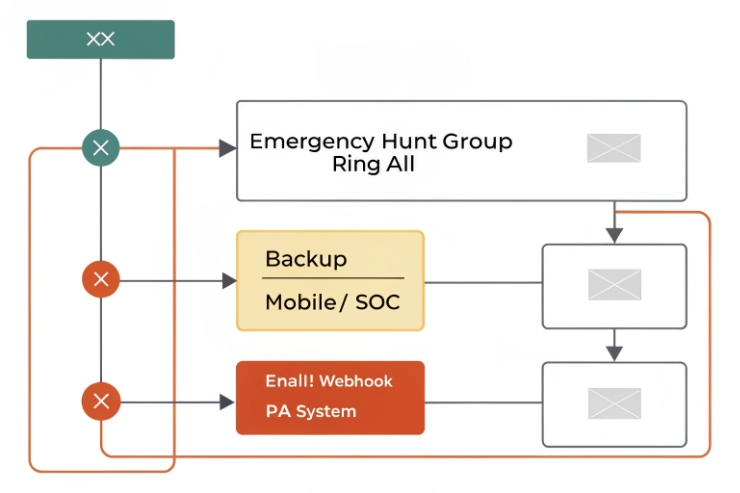

Keep emergency routing separate from normal calling

A common failure happens when emergency calls share the same trunk group, the same SBC policy, and the same queue rules as normal calls. The fix is separation:

-

separate dial plan match for emergency numbers and SOS calls

-

separate ring group or queue for dispatch

-

separate trunk or route for emergency (if PSTN/E911 is involved)

-

separate paging policy for emergency zones

One offshore job taught this lesson well. The system “worked” during normal tests. It failed during a drill because normal paging traffic was heavy. After the fix, emergency paging moved to a higher-tier multicast group, and the SIP SOS call used a special route with strict QoS. The next drill had clean alarms and clean audio.

The next step is to choose the SIP features that your PBX can actually enforce. This is where many specs become unrealistic. A clean spec stays aligned with real platform support.

Which SIP features enable priority and preemption—Resource-Priority, 911 routing, auto-answer, and barge-in on PBX/PAGA?

Emergency calls can lose to normal calls when SIP looks “equal.” Priority features add meaning to a call before it reaches the PBX.

Resource-Priority tags, dedicated emergency routing, auto-answer policies, and paging barge-in create a usable emergency workflow. Preemption needs PBX support, not only a phone setting.

Resource-Priority: make the call carry a priority label

Resource-Priority 2 is a SIP header concept that can signal call precedence. It does not make routers faster by itself. It makes SIP devices and proxies treat the call differently when rules exist. In practice, it is useful in two ways:

-

It marks an SOS call as “special” so the PBX can route it to the top

-

It allows a platform with true precedence features to apply preemption

A good approach is to tag only emergency calls, not all calls. If every call is “high,” then none is.

911 and emergency routing: keep it deterministic

Emergency routing has two jobs:

-

It must reach the right place every time

-

It must keep working during partial outages

For site safety, do not rely on a normal outbound route. Use dedicated emergency routing 3 and document it. In many plants, that means:

-

Send site emergency codes (like 110/119/911 equivalents) to a dedicated trunk or gateway

-

Send SOS button calls to dispatch, not to a normal receptionist group

-

Add retry and fallback rules, such as a second dispatch group or a radio gateway

Auto-answer: the control room must not miss it

Auto-answer is often more valuable than preemption. If dispatch phones auto-answer emergency calls with a warning tone, the operator hears it even when hands are busy. Many PBXs support auto-answer through paging features or special call classes. The safest practice is:

-

Enable auto-answer only on dispatch endpoints

-

Add a short warning tone or visual alert

-

Log the event for audits and drills

Barge-in: treat PAGA and paging as the “override channel”

Emergency voice often needs one-to-many delivery. That is where paging and PAGA systems shine.

-

“Barge-in” means the emergency page can interrupt a normal page or normal audio stream.

-

Many paging platforms support a priority ladder, like normal, urgent, and emergency.

If the plant uses PAGA, the design can be:

-

SIP phone triggers a PAGA input or SIP endpoint

-

PAGA plays an emergency tone and voice message

-

PAGA drives relays for beacons and sirens

A feature checklist that prevents bad surprises

| Feature | Phone role | PBX role | Paging role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource-Priority | send tag on SOS call | match tag, route to priority | not required |

| Emergency routing | dial SOS target | dedicated dial plan and trunk | optional |

| Auto-answer | optional | required on dispatch | optional |

| Barge-in | not required | optional | required for emergency override |

| Logging | event output | CDR and alarm logs | paging log |

Once SIP features are clear, the real work is PBX rules. Most issues come from dial plans, queue design, and what a platform can or cannot preempt.

How are priority rules set on Asterisk/FreePBX, 3CX, or CUCM—dial plan tags, call queues, and paging overrides?

A priority plan fails when it lives only in a diagram. It must exist as dial plan logic that stays readable after upgrades.

Asterisk/FreePBX usually delivers priority through dial plan separation and queue behavior. 3CX often uses dedicated queues and ring groups for emergency routing. CUCM supports structured precedence features when MLPP is enabled and endpoints are configured to honor it.

Asterisk and FreePBX: use separate call paths and keep them simple

Asterisk is flexible. That flexibility can create messy dial plans. The safest pattern is:

-

Create a dedicated emergency extension or feature code for SOS

-

Route it to a dedicated queue or ring group

-

Add rules to make it “jump the line”

-

Add a fallback target if the first group is busy or offline

Asterisk/FreePBX 4 can do this with outbound routes and inbound contexts. Many integrators use dial plan hooks to inject emergency behaviors without breaking GUI control. The key is to keep emergency logic in one place and document it.

A practical Asterisk idea is to tag an emergency call in SIP signaling and then route it:

-

Add a header like Resource-Priority for SOS calls

-

Check that header on the inbound side

-

Send it to a priority queue or a paging app

The emergency queue should avoid long hold music. It should ring dispatch endpoints fast. It should log every attempt.

3CX: treat emergency as its own queue and its own rule set

3CX 5 projects often succeed when emergency calls do not share the same ring group rules as normal calls. A common pattern is:

-

Create an “EMERGENCY” queue with the smallest possible agent list (dispatch only)

-

Route SOS and emergency codes straight into that queue

-

Use distinct ringtones and wallboard alerts so the operator sees it

-

Add a fallback to a second group or a mobile target if the first group fails

This approach is “priority,” not true preemption. It works well when dispatch staffing is designed correctly. If your spec demands “tear down existing calls,” then a pure queue model may not satisfy it.

CUCM: use MLPP when true precedence and preemption are required

Some environments require strict precedence and preemption. CUCM supports multilevel precedence and preemption using MLPP service features. When the design needs true preemption, CUCM is often chosen because it can enforce call levels across supported endpoints. The project still needs a clear policy:

-

who is allowed to place priority calls

-

which devices accept preemption

-

what tones and UI cues are required

-

how audit logs are retained

A planning table that helps choose the platform behavior

| Platform | Priority method | Preemption method | Best use case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asterisk/FreePBX | dial plan + queues + paging apps | possible with custom logic, not default | flexible sites, mixed equipment |

| 3CX | queues + ring groups + alerts | usually limited | office-like operations with strong UI alerts |

| CUCM | MLPP and policy controls | supported when configured | strict emergency precedence environments |

The cleanest approach is to write the acceptance test in plain words:

-

“SOS must ring dispatch within X seconds.”

-

“If dispatch is busy, the call must still connect.”

-

“If paging is active, emergency paging must override it.”

-

“All events must create logs.”

After PBX rules, paging is the next stress point. Paging is where “emergency-first” must stay true even when the plant is noisy and the network is busy.

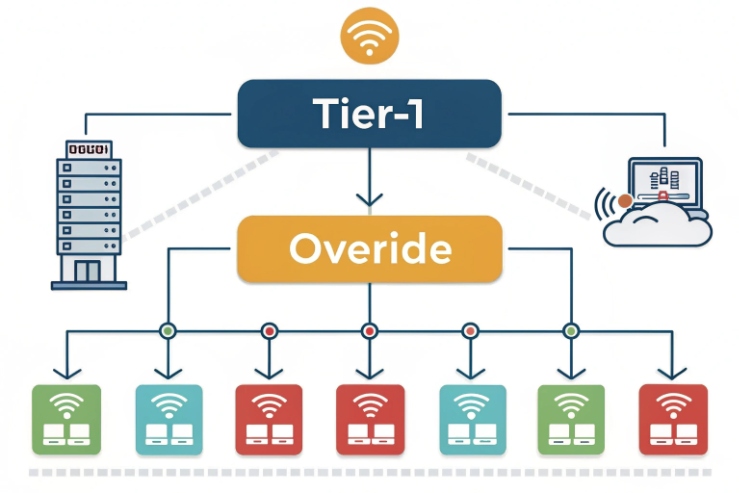

Can multicast paging tiers and zones enforce emergency-first delivery with fallback to unicast and local relay triggers?

Paging can save lives, but it can also overload a network when it is not planned. Emergency-first paging needs clear tiers and clean fallback.

Yes. Multicast paging tiers and zones can enforce emergency-first delivery when emergency uses its own multicast group, IGMP control is in place, and the system has fallback to unicast paging or local relay alarms if multicast fails.

Use separate multicast groups for each priority tier

A simple model is three tiers:

-

Tier 1: Emergency (highest)

-

Tier 2: Urgent

-

Tier 3: Routine

Each tier uses its own multicast paging 6 group address and its own permission rule. Emergency pages should have:

-

shorter setup path

-

higher QoS marking if supported

-

override permission in the paging controller

This design keeps routine paging from blocking emergency audio. It also makes troubleshooting easier because packet captures show which group is active.

Zones should match how people respond, not how cables run

Many projects define zones by cable trays or switch areas. That creates odd zones that confuse operators. A better zone design follows operational areas:

-

Process Unit A

-

Tank Farm

-

Loading Bay

-

Control Room perimeter

-

Muster points

When SOS is pressed, the system can:

-

start an emergency page in the local zone

-

start a second page to the control room zone

-

trigger beacon relays for visual alarms

Fallback logic: assume multicast can fail in harsh networks

Multicast can fail due to:

-

missing IGMP querier

-

snooping disabled or misconfigured

-

VLAN mismatch

-

ring topology convergence events

Emergency designs should include fallback:

1) Try multicast emergency page

2) If not confirmed, fall back to unicast paging to key endpoints

3) Trigger local relay outputs for beacon/siren as a last-resort local alarm

A relay trigger can drive:

-

a stack light

-

a siren

-

a PLC input that starts a plant-wide alarm plan

A simple paging design matrix

| Goal | Primary method | Fallback method | Local safety backstop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast one-to-many alert | multicast paging tier 1 | unicast paging to dispatch phones | beacon relay + PLC alarm |

| Local-only emergency | multicast zone page | direct SIP call to local team | strobe in the area |

| Network partial outage | local paging controller | local SIP PBX or SBC | hardwired relay alarm |

The paging controller should also provide event logs. The logs make drills easier to prove. They also help maintenance teams find IGMP and VLAN issues fast.

Now the last layer is QoS. Priority logic fails if packets arrive late. QoS keeps the emergency voice and event signals stable during traffic bursts.

What QoS settings ensure precedence—DSCP EF/CS5, VLAN voice profiles, and switch policies across industrial networks?

Emergency calls can be “priority” in the PBX and still sound broken if the network drops RTP. Voice needs stable delivery, not only good routing.

Use DSCP EF for RTP, mark SIP and emergency control signaling consistently, place phones on a voice VLAN, and enforce QoS at the switch edge with trust rules and queue policies that protect voice during congestion.

Mark RTP and signaling with a clear policy

A clean and common model is:

-

RTP media: DSCP EF

-

SIP signaling: CS3 or a site standard class

-

Emergency signaling: some sites use CS5 or a higher class for control signaling

The exact markings matter less than consistency. The switches must recognize the markings and map them to real queues.

Define the trust boundary at the access switch

Industrial networks often have mixed endpoints. Some endpoints mark packets correctly. Some do not. Some can be misconfigured. A safe rule is:

-

Trust Quality of Service 7 markings only on ports that are dedicated to voice endpoints and controlled devices

-

Rewrite or remark traffic from untrusted ports

If the site uses managed switches and voice VLAN profiles, enable the voice VLAN features where appropriate. Keep the voice VLAN separate from heavy data. This reduces jitter during bursts.

Ensure switching policies protect voice under congestion

QoS has value only when links can congest. Congestion happens on:

-

uplinks from remote cabinets

-

wireless bridges

-

ring or star aggregation points

-

WAN links between offshore and onshore

A practical switch policy uses:

-

strict priority queue for EF

-

bandwidth guarantees for signaling and control traffic

-

policing for best-effort traffic that can flood links

Multicast paging needs QoS and IGMP control too

Emergency multicast paging can carry large audio streams. If IGMP is not controlled, it can flood ports and add jitter. The network should:

-

enable IGMP snooping on the paging VLAN

-

ensure an IGMP querier exists where needed

-

rate-limit multicast where required

-

apply QoS to paging traffic, not only to RTP calls

A field-ready QoS checklist

| Item | Target | What to test in commissioning |

|---|---|---|

| DSCP marking | EF for RTP, standard for SIP | call quality during file transfer |

| Voice VLAN | separate from heavy data | jitter and loss at peak hours |

| Queue policy | priority for EF | no RTP drops on congested uplinks |

| IGMP | snooping + querier | paging works without flooding |

| End-to-end | same policy across hops | drill call from farthest cabinet |

A good acceptance test is simple:

-

Start an emergency page and an emergency SIP call at the same time.

-

Load the uplink with normal traffic.

-

Confirm that emergency audio stays clear.

-

Confirm that event alarms still arrive on time.

Conclusion

Emergency priority works when SIP tags, PBX rules, paging tiers, and QoS policies align. The system must prove fast ring, clear audio, and stable alarms during load and failures.

Footnotes

-

A guide to configuring dedicated lines for immediate emergency communication in industrial settings. ↩ ↩

-

Official standard defining SIP headers for communicating call precedence and priority levels. ↩ ↩

-

Insights into technologies used to ensure emergency calls reach the correct dispatchers without delay. ↩ ↩

-

The official site for the leading open-source communications platform and GUI management tool. ↩ ↩

-

Learn about 3CX, a software-based PBX providing advanced emergency routing and agent queues. ↩ ↩

-

Technical overview of IP multicast for distributing urgent audio alerts across multiple network zones. ↩ ↩

-

Comprehensive explanation of network mechanisms used to prioritize time-sensitive voice traffic during congestion. ↩ ↩