Outdoor keypads fail quietly. Water creeps in around one key, then dust sticks, contacts corrode, and emergency calls stop when people need them most.

A waterproof keypad is not one part. It is a sealing system: the key interface, the enclosure compression, the vent strategy, and the right IP validation tests working together.

Build the keypad like a sealing stack, not a button panel

Why keypads leak even when the enclosure is “IP-rated”

A weatherproof telephone enclosure 1 can be IP66 on paper, yet the keypad leaks because the keys are the most complex interface on the product. Each key press creates movement. Movement fights sealing. If a design depends on glue alone, or on a thin lip seal with low compression, water will eventually find a path.

A solid approach treats the keypad as a stack:

-

An outer barrier that blocks spray and dust.

-

A controlled compression seal between keypad and front panel.

-

A reliable switching method inside that stays dry even if the outer layer sees water.

-

A pressure equalization method so the enclosure does not “breathe” through the keys.

The three leak paths to kill first

1) Per-key leak path

This is the classic failure: water tracks along the moving key stem or around a key cap. The fix is to avoid exposed moving gaps and use a continuous outer membrane where possible.

2) Perimeter leak path

Even if each key is fine, water enters around the keypad frame. This is often torque, flatness, and gasket design. Corners and screw bosses are the weak zones.

3) Pressure pumping leak path

Sun heats the phone, air expands, then rain cools it quickly. That creates pressure cycles. Without a vent strategy, the system pulls air and moisture through the easiest path, often the keypad edges.

Key design principles that stay simple and reliable

-

Keep the outside surface continuous and easy to wipe.

-

Avoid deep key wells that collect water and dirt.

-

Design for controlled compression (consistent squeeze across the perimeter).

-

Separate “water barrier” from “electrical switching” so one failure does not kill the product.

-

Validate the sealing on the complete assembly, including cable glands and mounting orientation.

| Design goal | Best practical approach | Common mistake to avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Stop water at the interface | Continuous membrane surface | Individual key caps with exposed gaps |

| Keep tactile feel | Dome or pill design with stable travel | Too-soft rubber that bottoms out early |

| Prevent long-term leaks | Controlled perimeter compression | Over-torqued screws that warp the panel |

| Avoid breathing through keys | Proper vent membrane | No vent, then condensation and pumping |

If the sealing stack is clear, the next decision becomes easier: the switching method. Dome switches and membrane keypads both work, but each has trade-offs.

Now let’s break that down in a way that helps a real project spec.

Should I use sealed dome switches or a membrane keypad?

Keypad choices often get decided by feel or cost. That usually ends badly outdoors because feel and cost do not control water paths.

For high IP outdoor phones, a membrane-style outer barrier is usually the safest water solution, while sealed dome switches can work when each key is independently sealed and the perimeter seal is very controlled.

What “sealed dome switches” usually means in real products

A dome switch can be a metal dome on a PCB, or a rubber dome sheet with conductive pills. The key point is that the switch is inside the enclosure, and the seal must stop water before it reaches the switch. This can work well if:

-

the key travel is guided without creating a leak path,

-

each key has a lip seal or boot that does not tear,

-

and the outer surface drains well.

Many failures happen when the key stem rubs and slowly damages a seal lip. Outdoor dust acts like sandpaper. So if a design uses per-key boots, abrasion resistance becomes a real requirement.

What “membrane keypad” usually delivers

A membrane keypad 2 usually creates a continuous outer surface. That surface can be polyester (PET) overlay or a rubber membrane. It simplifies the water barrier because there are fewer moving gaps. It also makes cleaning easier, which matters in public and industrial sites.

The trade-offs are:

-

tactile feel can be less “clicky,” unless the structure includes dome switches 3 under the overlay,

-

some overlays degrade under strong UV unless the material and inks are chosen well,

-

and serviceability can be harder if the membrane is bonded.

How to choose fast for weatherproof telephones

A simple rule works in many outdoor SIP phone projects:

-

If the site is public-facing and cleaning is frequent, a membrane-style outer barrier reduces leak risk and reduces dirt traps.

-

If the site needs heavy gloves and very strong tactile feedback, a rubber keypad sheet with domes and conductive pills often feels better than a flat overlay.

| Option | Water sealing strength | Tactile feel | UV aging risk | Serviceability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET membrane overlay + internal domes | High (continuous surface) | Medium to good | Medium (material choice matters) | Medium (overlay replacement) |

| Silicone rubber keypad sheet + pills | High (continuous rubber) | Good | Low to medium | Good (replace sheet) |

| Individual key boots + internal domes | Medium (many seal points) | Very good | Medium | Medium |

| Exposed mechanical buttons | Low for outdoor IP | Very good | Medium | Easy, but risky |

In short: membrane-like outer layers are usually easier to make waterproof, while dome-based internal switching is easy to keep reliable if it stays dry.

The next question goes deeper into the most common “best of both worlds” approach: a one-piece silicone rubber keypad.

This is popular because it can seal well and still feel like a real keypad.

Can I design a one-piece silicone rubber keypad?

One-piece silicone keypads are tempting. They look simple, and they can handle weather. But a bad silicone keypad can still leak if the compression and venting are wrong.

Yes. A one-piece silicone rubber keypad can be an excellent waterproof solution when it uses a continuous sealing flange, stable key web geometry, and a controlled compression design around the perimeter.

The structure that works for outdoor sealing

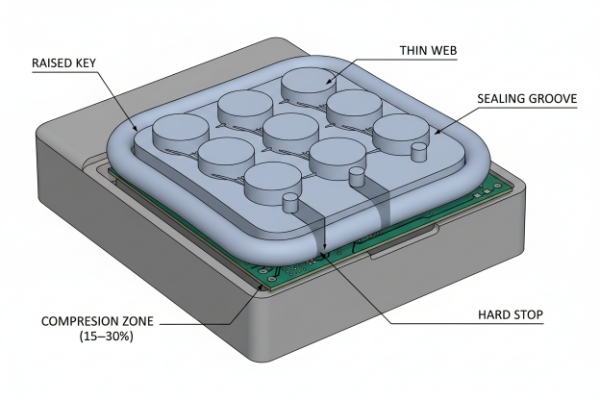

A strong one-piece silicone rubber keypad 4 usually includes:

-

A perimeter flange that seals against the front panel like a gasket.

-

Key webs that flex without tearing at the base.

-

Sealing ribs that create multiple barriers (not just one flat contact line).

-

An internal switching method (conductive pills or domes) that is protected from moisture.

The perimeter flange is where the real IP66 5 rating is won. If the flange is too thin, it will not hold compression set well. If it is too thick and soft, it can extrude when screws are tightened. The best designs use a groove or retainer feature so the gasket cannot walk during assembly.

Material and finish details that matter more than most people expect

-

Compound choice: silicone is strong for UV and temperature, but tear resistance varies by formulation. A higher tear strength compound often reduces long-term damage at the key roots.

-

Surface treatment: some silicone surfaces attract dust. Texture and coatings can reduce grime and improve cleaning.

-

Conductive pills: for pill-style switching, ensure stable contact pressure and avoid water paths around the pill pocket.

Design targets that keep the seal stable over years

-

Use consistent compression around the perimeter, not local crush near screws.

-

Avoid sharp edges on the housing that cut silicone during closing.

-

Include drain paths so water does not pool on the keypad surface.

-

Make the keypad replaceable if the project expects heavy use.

| Feature | Recommended approach | Why it helps waterproofing |

|---|---|---|

| Perimeter seal | Continuous flange + retainer groove | Stops frame leaks and prevents gasket walking |

| Key durability | High tear-strength silicone geometry | Reduces cracking at key roots |

| Switching | Internal domes or pills kept dry | Keeps electronics protected |

| Labeling | Molded legends or UV-stable inks | Prevents fading and peeling |

| Assembly | Controlled torque + stiff faceplate | Maintains even compression |

One-piece silicone is a strong option for weatherproof telephones, especially when the project needs glove-friendly keys, long UV life, and easy cleaning.

But even the best keypad can leak if the enclosure “breathes” through the keys during pressure changes. That is why venting is not optional for many outdoor sites.

Next is the part that most people skip: pressure equalization without creating a new leak path.

How do I vent pressure without leaking around keys?

Many keypad leaks are not direct spray leaks. They are pressure-cycle leaks. Heat expands internal air, then cooling creates suction. Without a vent, the phone tries to equalize through the weakest seal.

Use a dedicated vent element, like a waterproof breathable membrane vent, so pressure equalizes through a controlled path instead of pulling water through keypad edges and cable entries.

Why pressure changes attack keypad seals

Outdoor phones see fast thermal swings:

-

Sun heats the enclosure.

-

Rain cools it quickly.

-

Night cooling creates suction.

-

Wind pushes moisture into any micro-gap.

If pressure equalization has no controlled route, the system “pumps” air and moisture in and out through seams. Keys and cable glands become the pump valves.

Vent strategies that work without sacrificing IP

1) Waterproof breathable membrane vent

This is a common approach for outdoor enclosures. The breathable membrane vent 6 allows air exchange but blocks liquid water. Placement matters:

-

Keep it away from direct jet impact zones.

-

Place it where water cannot pool.

-

Protect it with a hood or labyrinth feature if needed.

2) Labyrinth vent path with hydrophobic barrier

If a vent must be protected, a labyrinth can reduce direct water exposure. This is useful in public areas where vandal risk is high.

3) “No vent” approach (only for limited cases)

A fully sealed enclosure can work, but it increases stress on gaskets and increases condensation risk if any moisture is trapped during assembly. This approach demands strong process control and often still benefits from a controlled vent.

How to avoid vent-related leaks

-

Do not vent near the keypad perimeter.

-

Do not vent on the bottom where splash and pooling are common.

-

Keep vent adhesives and surfaces clean and consistent.

-

Validate the vent performance after environmental aging, not only on day one.

| Vent approach | Best use case | Key risk to manage |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane vent | Most outdoor SIP phones | Placement and protection from jets |

| Labyrinth + membrane | Public areas + harsh wash | Complexity and clogging risk |

| Fully sealed, no vent | Controlled indoor/outdoor mild swings | Pressure stress + condensation |

A controlled vent strategy reduces leakage risk and also reduces fogging and condensation, which directly improves audio consistency.

Once the design choices are made, proof matters. Buyers and clients will ask, “How do you know it works?” The right answer is IP testing focused on the keypad as an assembly, not a single part.

So the final piece is validation: which IP tests prove keypad sealing success.

What IP tests validate my keypad sealing success?

A keypad can pass a bench splash check and still fail in real rain or cleaning. IP validation gives you a shared language with clients and tender reviewers.

Validate keypad sealing with IEC 60529 water tests that match your site: IPX5/IPX6 for spray and jets, and IPX7 for temporary immersion if flooding risk exists. Combine this with dust tests (IP5X/IP6X) to confirm long-term keypad reliability.

Choose tests based on the water event you face

Spray and jets

For outdoor telephones that face storms, hose rinse, or washdown from a distance, jet and spray tests are the right proof. These tests focus on water ingress under directed spray, which is where keypad edges and audio ports get punished.

Immersion

If the phone can be temporarily submerged because of low mounting or drainage overflow, immersion tests matter. Immersion does not replace jet tests. It covers a different event.

Dust

Dust testing is critical for keypads because dust can:

-

wear seals during key travel,

-

stick to wet surfaces and create wicking paths,

-

and reduce tactile feel over time.

How to define pass/fail so the test matches a telephone

A good keypad pass/fail plan includes:

-

No harmful water ingress into the enclosure.

-

No water reaching the PCB in a way that causes corrosion risk.

-

Key function remains stable: consistent actuation, no sticking keys.

-

Audio remains acceptable if the keypad area is near speaker or mic paths.

Testing sequence that avoids false confidence

-

Run a functional keypad test before IP testing.

-

Dry the unit naturally, then retest function.

-

Open only dedicated sample units to inspect internal water paths, so production units are not damaged.

| Site reality | Minimum water test set | Add-on tests that reduce surprises |

|---|---|---|

| Outdoor rain + wind | IPX5/IPX6 8 style water tests | IP6X dust + UV aging of keypad materials |

| Hose rinse / cleaning | Jet-focused water tests | Chemical wipe resistance + key travel endurance |

| Flood-prone low mount | Jet test + IPX7 9 immersion | Condensation cycling + vent verification |

| Public space vandal risk | Same as above | IK impact 10 checks for faceplate and key damage |

How to explain validation to clients in one clean line

The easiest client message is:

- “The keypad is validated by IP water tests that match your cleaning and weather, and dust tests that match your environment. Function is checked before and after.”

This keeps the discussion on real site threats, not marketing words.

Conclusion

Waterproof keypads come from a continuous barrier, controlled compression, proper venting, and IP tests that match spray, jets, dust, and immersion risks.

Footnotes

-

Housing designed to protect telecommunication equipment from environmental hazards like moisture. [↩] ↩

-

Interface using pressure-sensitive flexible surfaces to activate circuits without moving parts. [↩] ↩

-

Tactile metal or rubber components providing snap-action feedback for electronic switches. [↩] ↩

-

Molded elastomeric interface offering a continuous, weather-resistant surface for user input. [↩] ↩

-

Standard classification defining the level of protection against dust and high-pressure water jets. [↩] ↩

-

Component allowing airflow to equalize pressure while blocking liquid water ingress. [↩] ↩

-

International standard specifying degrees of protection provided by enclosures (IP Code). [↩] ↩

-

Test ratings verifying protection against low-pressure and high-pressure water jets. [↩] ↩

-

Rating confirming equipment protection against the effects of temporary water immersion. [↩] ↩

-

Standard measurement indicating the level of protection against external mechanical impacts. [↩] ↩