Offshore sites punish weak equipment. Salt, vibration, and fast weather changes can turn a “working” phone into a silent box when crews need it most.

Yes. Explosion-proof telephones can be used offshore when the Ex rating matches Zone 1/2 and IIC needs, the corrosion strategy matches marine exposure, the SIP system is redundant, and installation uses certified glands, bonding, and surge protection.

Offshore-ready Ex telephones need one spec that covers safety, corrosion, and uptime?

Offshore acceptance is easier when the project team treats the telephone as both a hazardous-area device and a marine reliability device. The Ex certificate is only one part. Offshore adds corrosion class targets, class society expectations, and a harder maintenance reality. A phone that needs frequent field work becomes expensive because permits and access are slow.

A stable offshore spec starts with three “non-negotiables”:

- Correct hazardous-area marking for the location and gas risk.

- Corrosion and sealing plan that matches salt spray, UV, and washdown.

- System uptime plan that includes redundant SIP and clear alarm actions.

Then the spec adds “operational” requirements:

- Loud and clear audio in wind and machinery noise.

- Parts that can be replaced fast, with a small spare kit.

- Remote monitoring so the control room sees faults before a crew finds them by accident.

In offshore projects, the best results come when each phone location gets a simple label like:

- “Helideck: outdoor, high wind, high salt, high noise.”

- “Process deck: Zone 1, vibration, cable runs near drives.”

- “Accommodation: Zone 2, lower noise, easier access.”

That location label makes the choice clear for housing material, cord type, glands, and monitoring.

What an offshore tender reviewer usually checks first

A tender reviewer often looks for proof that the product can be accepted on an offshore unit without repeated rework. That means the submission should show the Ex certificate set, the ingress and impact rating, and any requested marine type approval route. It should also show the corrosion approach and the maintenance plan.

| Offshore requirement | What the phone must show | What the project should document |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard safety | ATEX 1/IECEx 2 marking fits Zone and IIC needs | Location list and required markings |

| Marine durability | Corrosion strategy and sealing method | Coating, material, gasket statement |

| Uptime | Redundant SIP and monitoring alarms | Failover plan and alarm matrix |

| Maintenance | Serviceable parts and access | Spare kit and replacement steps |

A strong spec prevents the most common offshore mistake: buying a phone that is “Ex-rated” but not truly “offshore-ready.”

The next sections break the offshore question into four parts: certifications, materials, integration, and installation practices.

Which certifications suit offshore hazardous areas?

Offshore projects move fast. A missing certificate can stop installation in one day, even if the phone is already on the deck.

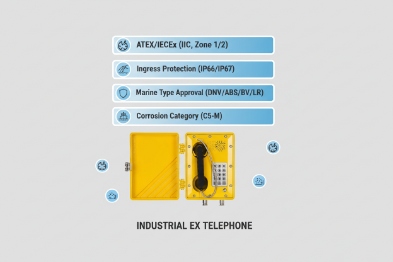

Offshore Ex telephones usually need ATEX or IECEx for Zone 1/2, often with IIC options and a suitable temperature class. Many operators also ask for marine acceptance support like DNV or ABS type approval paths, plus IP66/IP67 sealing and a marine corrosion target such as C5-M or the newer CX exposure class.

Ex marking: Zone 1/2 and IIC are the core offshore language

Most offshore hydrocarbon areas use Zone concepts. A phone for process areas often targets Zone 1 or Zone 2. The gas group can be IIA, IIB, or IIC, based on the site risk. On rigs and production platforms, IIC is often preferred as a conservative choice when the risk profile is broad.

Temperature class matters because topside areas can be hot and sun-exposed. T6 is stricter than T4. The site safety team decides the class. The phone should match that site decision.

Marine type approval: why it shows up in offshore tenders

Many offshore units operate under class society oversight. In these tenders, the buyer may ask for evidence that equipment acceptance will be smooth. That is where type approval language appears. ABS 3 states that type approval is used to streamline acceptance of equipment and components on marine and offshore applications. DNV 4 also offers type approval and related services for communication systems. These routes do not replace Ex certification. They support offshore acceptance workflows.

Corrosion class language: C5-M and the newer CX

Offshore buyers often use corrosion class terms like “C5-M.” ISO 12944 updates changed how these categories are described. Older C5-M and C5-I terms have been combined and extended, and offshore exposure is often described under “CX” in newer ISO 12944 parts. A practical tender spec can accept “C5-M or equivalent” while also asking for a coating system aligned with the newest ISO 12944 5 approach.

| Certification or rating | What it proves offshore | What to ask for in a tender pack |

|---|---|---|

| ATEX / IECEx | Safe use in hazardous gas zones | Certificate, marking, conditions of use |

| Zone 1/2 + IIC | Fit for common offshore gas risks | Exact marking, gas group, temp class |

| IP66/IP67 | Water and dust resistance baseline | Test summary and what the rating covers |

| DNV / ABS type approval route | Easier acceptance on classed units | Type approval status or plan and scope |

| Marine corrosion class | Coating and material suitability | Coating system description and salt exposure plan |

Offshore approvals become simple when the tender pack shows the exact markings and also shows how the product fits the marine acceptance process. The next risk is not paperwork. It is salt, UV, and temperature. That risk is solved by the material and coating choices.

Do 316L housings and marine-grade protection survive salt spray, UV, and –40°C to +70°C on rigs?

Offshore corrosion is not slow. It attacks edges, screws, and cable entries first. UV then weakens plastics and seals.

Yes, but only when the full build is designed for marine exposure. A 316L or equivalent corrosion-resistant housing helps, but coatings, fasteners, gaskets, and cable entry sealing decide real life. A –40°C to +70°C range is realistic when the handset, cord, and seals are also rated for it.

Housing material: 316L is a strong base, but not a full solution

316L stainless steel 6 resists many marine corrosion modes better than basic metals. Still, offshore failures often happen at joints and hardware, not on the flat panel. Screws, hooks, spring parts, and gland bodies must be corrosion resistant too. A single low-grade fastener can become the first rust point and then damage sealing.

Some offshore designs also use marine-grade aluminum with heavy coatings. That can work when coating quality is high and edges are protected. The key is controlling damage from knocks and tool contact.

Coatings: choose a system that matches offshore exposure class

Coatings should be specified as a system, not as a brand name. The system should include surface preparation and dry film thickness targets. Offshore topsides can align with very high or extreme corrosivity categories in ISO 12944 language. Many buyers still say “C5-M.” It is also smart to mention the newer “CX” approach for offshore exposure when the project uses updated ISO references.

Seals and gaskets: chemical and UV resistance matters

A phone can be IP66 7 on day one and still leak after seal aging. Seal material choice must match:

- UV exposure on helideck and open decks

- Temperature swings and cold wind

- Cleaning chemicals used during shutdown

- Oil mist and hydraulic fluid exposure near machinery

Silicone gaskets stay flexible in cold and heat. Neoprene can handle many oils well. The right answer depends on the area.

Handset and cord: the offshore weak point

Many offshore “phone failures” are actually cord failures. Coiled cords are convenient, but they concentrate stress near the ends. Armored umbilicals resist cuts and abrasion, but they need correct glands and bonding. A strong offshore handset assembly includes strain relief, a sealing method that stays tight, and a service plan with replaceable parts.

| Offshore stress | Typical failure mode | Design choice that prevents it | Field check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salt spray | Rust on screws and hook | Anti-corrosion fasteners and hook | Visual inspection schedule |

| UV | Seal cracks, plastic fades | UV-rated materials and gasket choice | Monthly quick look on open decks |

| Cold wind | Cord stiffening and cracking | Low-temp rated cord and boot | Bend test during maintenance |

| Heat and sun | Seal compression set | Gasket with low compression set | Check water ingress signs |

| Washdown | Leak at cable entry | Correct gland and face seal | Spray test at commissioning |

A good offshore build survives because every exposed part is marine-ready, not only the main housing. When materials are right, the next step is system integration. Offshore teams want the phone to be part of PA/GA, PBX, and emergency signaling.

How do Ex telephones integrate with PA/GA, SIP PBX, and emergency beacons offshore?

Offshore operations rely on fast announcements and clear escalation. A phone that only calls one number is not enough for many rigs.

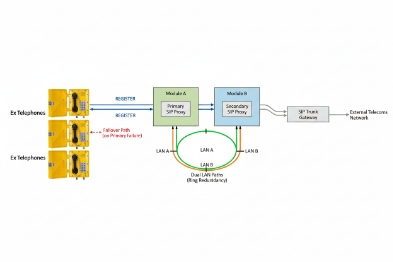

Offshore Ex telephones integrate through SIP PBX registration, multicast paging for PA/GA-style announcements, relay outputs for beacons and alarms, and redundant SIP proxies for continuity. The best design uses simple call flows that crews can use under stress.

SIP PBX integration: keep call flows simple

Offshore call flows should be short. People wear PPE and gloves. Stress is high during incidents. A good offshore dial plan uses:

- One-touch emergency call to CCR (Central Control Room)

- Group ring for the safety team

- Hotline or auto-answer for critical stations

- Clear location-based caller ID naming

Redundancy matters. Many offshore networks use two SIP proxies or two call servers. The phone should support primary and secondary proxies and automatic failover rules that do not flap.

Multicast paging: the bridge to PA/GA behavior

Multicast paging is common in industrial paging because it scales well. Offshore paging needs low delay and clear audio. A phone that can join multicast groups supports:

- Muster announcements

- Area broadcasts to a deck or module

- Maintenance paging during shutdown

Multicast should be planned with VLAN and QoS. Voice packets must not compete with camera streams on uplinks.

Relay outputs and inputs: simple links to alarms

Relays are still a clean way to connect VoIP endpoints to offshore safety signals.

- A relay output can drive a local beacon or horn.

- An input can read a door contact, a manual alarm button, or a system status.

A simple alarm pattern works well: “SIP offline” triggers a relay output, which triggers a local beacon and also feeds a PLC input for the CCR screen.

Redundant SIP and power: design for partial failures

Offshore units handle failures, not perfection. The phone should keep a clear state:

- Registered to primary

- Registered to secondary

- Offline but link up

- Link down / power fault

That state should be visible to monitoring tools and should trigger the right action.

| Integration need | Feature | Offshore value | One practical rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency calling | SIP 8 hotline and group ring | Fast contact to CCR | Keep dial plan short |

| PA/GA-style paging | Multicast paging 9 | One-to-many announcements | Use QoS and VLAN separation |

| Local alarms | Relay outputs | Beacon and horn triggers | Latch alarms with reset policy |

| Continuity | Redundant SIP proxies | Keeps service during server loss | Avoid rapid flip-flop timers |

Integration looks good on paper when it is demoed. It works offshore only when the installation and network details are correct. That is why the final part is the most important: installation practices that reduce failure on helideck and process areas.

What installation practices reduce failure on helideck and process areas?

Offshore failures often come from small installation shortcuts. A wrong gland, a weak bond, or poor surge practice can destroy uptime.

The best offshore installation uses Ex-certified glands matched to the entry thread, armored cabling where needed, solid earthing and bonding, PoE surge protection on long runs, and a maintenance approach that allows safe access without long downtime.

Ex-certified glands and correct cable entries

Cable entry is a common failure point offshore because water and salt attack the interface. The gland must match:

- The phone entry thread (Metric or NPT)

- The cable type (armored or not)

- The hazardous area concept required

Armored cable terminations must clamp armor correctly. The goal is strain relief and correct bonding. If armor is not terminated properly, the cable can move and the seal can fail.

Earthing and bonding: keep it short and clean

Bonding should be metal-to-metal and low impedance. Paint can block bonding. Corrosion can also weaken bonding points over time. A routine check for bonding continuity prevents hidden faults.

On helidecks, high winds and constant salt can loosen small hardware over time. Fasteners should be locked and corrosion resistant. Maintenance teams should include a quick torque check routine for exposed stations.

PoE surge protection and EMC discipline

Offshore cable routes can run near large motors and switching loads. PoE ports are sensitive to surges and transients. A layered surge plan helps:

- SPD at the network cabinet entry for long runs

- Secondary protection closer to the endpoint when needed

- Short and direct grounding path for the SPD

Shielded cabling can help, but only with correct shield bonding. A floating shield can make noise worse.

Maintenance access and workflow design

Access is a real cost offshore. A good plan includes:

- A spare kit near the module: handset, cord, gasket set, and one spare unit

- Clear labeling of VLAN, port, and extension on the mounting plate

- A maintenance bypass plan for network or PBX work

- A defined emergency auto-dial workflow with guardrails

Auto-dial can be helpful for unmanned points, but it must not create nuisance calls during maintenance. A safe rule uses long-press triggers, a cooldown timer, and a maintenance disable mode.

| Location | Main risk | Installation focus | Quick commissioning test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helideck | UV, wind, salt, washdown | Coating, glands, loud audio, cord strain relief | Spray test + test call to CCR |

| Process deck | Zone risk, vibration, EMI | Bonding, armored cable, surge, QoS | SIP failover + RTP audio test |

| Utility areas | Mixed exposure | Correct labeling and access | SNMP 10 health + alarm beacon test |

| Accommodation edge | Lower risk but high use | Clear dial plan and spare handset | Hotline and group ring test |

When these practices are followed, offshore phones behave like safety equipment, not like fragile IT endpoints. That is the point. Crews should trust the phone under stress, and maintenance should be predictable.

Conclusion

Explosion-proof telephones work offshore when Ex marking, marine corrosion design, redundant VoIP integration, and disciplined installation are planned as one system.

Footnotes

-

ATEX EU directives regulating equipment and protective systems intended for use in potentially explosive atmospheres. ↩

-

IECEx International certification system for equipment used in explosive atmospheres, facilitating global trade. ↩

-

ABS American Bureau of Shipping; a classification society providing type approval for marine and offshore equipment. ↩

-

DNV Det Norske Veritas; a global quality assurance and risk management company providing classification and type approval. ↩

-

ISO 12944 International standard for the corrosion protection of steel structures by protective paint systems. ↩

-

316L stainless steel A low-carbon version of 316 stainless steel, offering high resistance to corrosion, especially in marine environments. ↩

-

IP66 Ingress Protection rating indicating the enclosure is dust-tight and protected against powerful water jets. ↩

-

SIP Session Initiation Protocol; a signaling protocol used for initiating, maintaining, and terminating real-time sessions. ↩

-

Multicast paging A network efficiency method where a single audio stream is sent to a group of IP devices simultaneously. ↩

-

SNMP Simple Network Management Protocol; a standard for collecting and organizing information about managed devices on IP networks. ↩