Oil mist and greasy hands can turn a rugged phone into a leaking, sticky, unreliable device. That risk grows fast when emergency calls depend on one keypad.

Oil contamination resistance is built through the right housing material, oil-tolerant seals, verified lab tests, and simple maintenance rules that protect IP66/67 sealing and long-term keypad feel.

Oil Contamination Resistance Is a System, Not a Single Material

Oil exposure is more than “splash”

Refinery and chemical sites rarely expose a phone to one clean fluid. The phone sees hydraulic oil, diesel, lubricants, cleaning agents, and airborne hydrocarbons. Some exposure is direct splash. Some exposure is slow. Oil mist settles on the keypad every day. A technician touches the phone with gloves covered in grease. The enclosure looks fine, but the seal line keeps absorbing and relaxing. After months, the gasket can swell, soften, or take a compression set. Then the IP66/67 sealing 1 becomes fragile in real life.

A serious oil-resistance plan starts by listing where oil can enter. The main entry points are always the same: the keypad perimeter, the hook switch area, the handset cord entry, and the cable gland. Oil can also creep into small gaps at the front cover, around screws, and under label windows. A metal enclosure does not stop this. The seal design stops it.

Oil resistance also has a functional side. A phone can remain sealed but still become hard to use. Keycaps can swell. Rubber keypads can become soft and sticky. Printing can fade. A hook switch can drag. These failures hurt emergency readiness even if water does not enter.

This is why the best projects define oil resistance with clear acceptance rules:

-

No cracks, no sticky surfaces, no severe swelling

-

No loss of IP performance

-

No loss of key feel and hook function

-

No change that causes false key presses or missed dialing

| What “oil resistance” must protect | What can go wrong | What a good spec prevents |

|---|---|---|

| Sealing line | Gasket swell, compression set | Slow leaks and IP failures |

| User interface | Sticky keys, soft elastomer | Slow dialing and missed calls |

| Cable entry | Gland softening and slip | Water and dust entry at the worst point |

| Finish | Paint attack and underfilm corrosion | Long-term rust and peeling |

A phone becomes oil-robust when the materials and the design work together, and when the test plan matches the real fluids on site.

The next sections show how to choose materials, how to test, how oils threaten IP66/67 sealing, and how maintenance keeps performance stable year after year.

A practical way to keep procurement and engineering aligned

Some buyers ask for “oil proof.” That is not a standard claim. A better approach is to ask for “oil contamination resistance” and then list the fluids, the temperature, and the duration. IEC 60068-2-74 is often used as a reference method for fluid contamination exposure, since it provides a structured procedure for accidental contact with fluids.

One more point matters for B2B deployments. OEM projects often change keypad materials, paint color, and gasket type for branding. Those changes can break oil resistance if the supplier does not re-validate. That is why our team prefers a short material-control list in the contract. It keeps the product stable across batches.

If oil resistance matters on your site, it is worth reading the next section carefully, because the material choices decide most of the outcome before testing even starts.

Which materials and finishes provide oil resistance—316L, GRP, powder-coated aluminum, and fluorocarbon/EPDM gaskets?

Oil resistance starts with the parts people cannot see. A wrong gasket can defeat a perfect enclosure.

316L stainless, quality GRP, and well-prepared powder-coated aluminum can all resist oils, but the real success depends on gasket chemistry, surface prep, and stable compression at seams and glands.

316L stainless steel: strong baseline for refineries

316L stainless 2 is a common choice for harsh industrial zones because it resists corrosion and holds its surface under cleaning. It also tolerates oily films without softening or swelling. The main risk is not the metal. The risk is what is attached to the metal. A stainless enclosure still needs gaskets, keypads, labels, and cable glands. Those parts define oil resistance over time.

316L also helps with long-term sealing because it keeps flatness and thread integrity. Screws stay tight. Cover pressure stays stable. That reduces “micro breathing” at the seam.

GRP: good chemical tolerance, but details matter

Glass reinforced plastic (GRP) 3 can be very stable in many chemical environments. It does not rust. It can be molded into thick walls that support sealing compression. Still, GRP performance depends on resin system, filler, and surface finish. Some oils can stain the surface. Some cleaning agents can dull it. If the site uses aggressive degreasers, GRP should be matched to that cleaner list.

GRP also needs attention at inserts and fastening points. If a metal insert loosens, the seal load changes. Then oil ingress risk rises. Choosing the right housing material 4 is critical for long-term reliability in refineries.

Powder-coated aluminum: durable only with correct prep

Powder-coated aluminum can be a cost-effective housing choice. It can resist many oils when the coating system is correct and the surface prep is clean. The main failure mode is coating undercutting at edges and scratches. Oil and cleaners can creep under a weak coating, then corrosion starts beneath the film. This is why edge design, coating thickness, and curing control matter.

Gaskets: fluorocarbon vs EPDM is not a small detail

For oil-heavy environments, fluorocarbon (often called FKM/Viton-type) is widely used because it generally resists many oils and fuels better than many general-purpose elastomers. EPDM is strong for weather and water, but it can be weaker with many petroleum oils. A refinery phone usually benefits from fluorocarbon at key sealing lines, especially at glands and keypad perimeters. Still, fluorocarbon is not a magic answer. It must match the oil type and temperature.

| Component | Better choice for oil-heavy sites | What to avoid | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main cover gasket | FKM/fluorocarbon | Low-grade rubber blends | Swell and compression set cause leaks |

| Keypad seal | Oil-resistant silicone or FKM-based | Soft EPDM for petroleum contact | Sticky keys and seal drift |

| Cable gland seal | Oil-rated elastomer | Unknown gland materials | Gland is the most common leak point |

| Coating | Industrial powder system | Thin paint with weak adhesion | Underfilm corrosion and peeling |

In real projects, material selection also includes small details: keypad ink type, label adhesive, and handset cord jacket. Oil can attack those quickly. A good supplier can provide a material list and basic compatibility notes so the integrator does not guess.

What tests verify oil resistance—ASTM D471/ISO 1817 swelling, IEC 60068 contamination, and accelerated aging?

Many “oil resistant” claims are only based on material datasheets. That is not enough for hazardous sites.

Oil resistance is verified by elastomer immersion tests like ASTM D471 or ISO 1817, plus fluid contamination methods like IEC 60068-2-74 and aging cycles that check sealing, keypad feel, and finish after exposure.

Elastomer swelling and property change: the core proof for seals

Most oil-related failures begin with elastomers. That includes gaskets, keypad mats, cable gland seals, and O-rings. The most direct way to verify is immersion testing and property comparison before and after exposure.

ASTM D471 5 is a common method used to evaluate how rubber changes when exposed to liquids. It covers procedures to compare how rubber compositions withstand the effects of liquids.

ISO 1817 6 describes methods to evaluate resistance of vulcanized or thermoplastic rubbers to liquids by measuring properties before and after immersion in test liquids, including petroleum derivatives and solvents.

For procurement, the best practice is to request:

-

Volume change (swell) after defined time and temperature

-

Hardness change

-

Tensile change or elongation change when relevant

-

Compression set testing if the gasket is under long-term load

These numbers predict if the gasket will hold compression and keep IP rating.

Fluid contamination exposure: test the assembled product behavior

Immersion tests do not capture all real-life contamination. A phone can be splashed, wiped, and heated. Oil can sit on one corner and creep. IEC 60068 7 -2-74 provides a structured method for testing the ability of equipment or materials to withstand accidental contact with fluids.

A useful approach is to apply the relevant oils or reference fluids to:

-

keypad surface and perimeter

-

hook switch area

-

cable gland area

-

enclosure seam line

Then the phone is inspected and function-tested.

Accelerated aging: where hidden weaknesses show up

Oil resistance is not only about immediate swelling. It is also about long-term changes. Aging can combine:

-

temperature cycling (hot day, cool night)

-

UV exposure if outdoors

-

repeated cleaning with approved cleaners

-

repeated key presses after oil exposure

The acceptance checks should include both sealing and usability:

-

IP66/67 retest or focused leak checks

-

keypad actuation force consistency

-

hook switch operation

-

cable gland torque retention

-

cosmetic changes that affect readability and safety markings

| Test family | What it proves | What a strong report includes |

|---|---|---|

| ASTM D471 / ISO 1817 | Elastomer compatibility with oils | Swell %, hardness change, time/temp |

| IEC 60068-2-74 | Assembled material tolerance to fluids | Photos, pass/fail criteria, notes |

| Aging cycles | Stability over time | Before/after function logs and checks |

| IP verification | Seal integrity after contamination | IP test results or equivalent leak test |

A supplier that can show these tests reduces project risk. It also speeds up approval with end users and EPC teams. In our OEM work, a short test plan tied to real fluids usually prevents costly redesign after site feedback.

How do oils impact IP66/67 sealing—gasket swell, compression set, and cable gland integrity in refineries?

IP66/67 can look perfect in a clean lab. Oil contamination is what makes sealing fail slowly in a refinery.

Oils can soften or swell gaskets, increase compression set, and reduce friction in cable glands, which weakens IP66/67 sealing over time even if the phone passes initial IP tests.

Gasket swell changes the sealing geometry

A gasket is designed for a target compression. Oil absorption can swell an elastomer and change its shape. A small swell can increase compression at first. That can feel like “better sealing.” Then the gasket relaxes. The material loses elasticity. The seal line becomes uneven. After that, the gasket can take a permanent set. The cover torque stays the same, but the seal force drops.

This is why compression set is a key metric. If a gasket takes a set, it does not rebound after vibration or temperature changes. The phone can start to “breathe” at the seam. Dust enters first. Water follows later.

Keypad and hook switch areas are high-risk zones

Oil hits the front panel most. If the keypad uses a rubber mat, oil can change its hardness and surface feel. Keys can become sticky. A sticky key makes operators press harder. That adds more stress to the perimeter seal. The hook switch can also attract oil and dust. That mix can form a paste that increases friction. If the hook switch does not return cleanly, hotline and emergency behavior becomes unreliable.

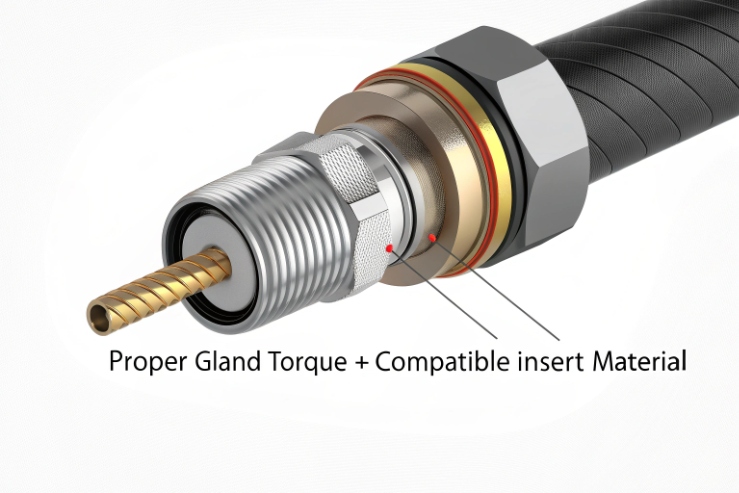

Cable glands are the silent failure point

Many IP issues come from the cable entry, not the main cover. Oil can migrate along the cable jacket and sit at the gland. If the gland elastomer is not oil-rated, it can soften. If it swells, it can lose grip. The cable can move under vibration. That creates a leak path. The gland thread can also loosen if the material creeps.

A refinery should treat gland selection as part of the phone spec:

-

oil-rated gland seals

-

proper thread seal method for the enclosure type

-

correct torque and strain relief

-

cable jacket compatibility

| Sealing area | Oil-driven failure mode | What to specify |

|---|---|---|

| Main cover seam | Swell then compression set | FKM gasket, controlled compression |

| Keypad perimeter | Sticky surface, seal drift | Oil-tolerant keypad + stable frame |

| Hook switch | Dirt paste, mechanical drag | Protected geometry and easy cleaning |

| Cable gland | Softening, cable slip, leak path | Oil-rated gland and jacket match |

Oil contamination is not random. It follows gravity, vibration, and touch points. A good design reduces oil pooling, keeps seal loads stable, and makes cleaning simple.

What maintenance practices sustain performance—approved cleaners, anti-oil coatings, and scheduled gasket/keypad replacement?

Even the best design will drift if maintenance uses the wrong cleaner or ignores early gasket changes.

Performance stays stable when sites use approved cleaners, avoid aggressive solvents, inspect glands and seams, and replace high-wear parts like keypads and gaskets on a simple schedule.

Approved cleaners prevent slow damage

Many site teams use strong degreasers because they work fast. Some degreasers also attack plastics, inks, and elastomers. The result is fading labels, brittle keypad surfaces, and seals that lose elasticity. A better method is a short approved cleaner list that matches the phone materials. The list should include:

-

mild detergent solutions

-

neutral pH cleaners where possible

-

limited-use solvents with clear rules

-

wipe-down steps that do not force fluid into seams

A simple rule helps: cleaning must remove oil without soaking the seal line.

Anti-oil surface strategies reduce daily buildup

Some sites add protective films or coatings. The best strategies are ones that do not change Ex safety markings and do not block acoustics:

-

hydrophobic or oleophobic coatings on exposed metal surfaces where allowed

-

textured surfaces that reduce smear visibility

-

keypad designs that shed oil and do not trap dirt at edges

Coatings are not a replacement for good gaskets. They only reduce the load on cleaning and slow down grime buildup.

Scheduled replacement beats emergency repairs

Keypads and gaskets are wear items in oil-heavy areas. Replacing them on schedule is cheaper than downtime. The schedule depends on exposure, but the logic is simple:

-

inspect quarterly in high-oil zones

-

replace when key feel changes or surface becomes sticky

-

replace if swelling or cracks appear

-

retorque and inspect glands during the same visit

| Maintenance task | Simple interval | What to record |

|---|---|---|

| Visual wipe-down and check | Weekly to monthly | Oil pooling points and key feel |

| Gland inspection and retorque | Quarterly | Cable movement and seal condition |

| Keypad inspection | Quarterly | Stickiness, legibility, false presses |

| Gasket replacement | 12–36 months (site dependent) | Seal condition and IP check results |

Small habits that extend life

A few habits keep phones stable:

-

keep spare gasket and keypad kits in the maintenance store

-

train technicians to avoid prying tools at seal lines

-

keep cable strain relief correct so glands do not carry pull load

-

log any reset or odd behavior after cleaning, since cleaner choice can be the cause

For OEM and large deployments, a supplier can also provide a “cleaning and inspection card” that matches the actual materials shipped. That removes guesswork across different sites and contractors.

Conclusion

Oil resistance comes from oil-tolerant seals, compatible housings and finishes, real fluid tests, and simple maintenance that protects gaskets, keypads, and cable glands over time.

-

Learn about IP66 and IP67 ratings and how they define equipment protection against water and oil ingress. ↩ ↩

-

A technical overview of 316L stainless steel properties and its excellent resistance to chemicals and corrosion. ↩ ↩

-

Insights into the benefits of using glass reinforced plastic (GRP) for durable industrial equipment in harsh environments. ↩ ↩

-

Choosing the right housing material ensures that electrical enclosures can withstand the chemical stress of refinery operations. ↩ ↩

-

The ASTM D471 standard provides a testing framework for evaluating the resistance of rubber materials to liquid exposure. ↩ ↩

-

Official ISO standard for determining the resistance of vulcanized or thermoplastic rubber to the action of liquids. ↩ ↩

-

IEC 60068 is a suite of standards for environmental testing of electronic products, including resistance to fluid contamination. ↩ ↩